This is me on 30th July 2025 at my graduation ceremony at King’s College London proudly receiving my Post-Graduate Diploma in Psychology and Neuroscience of Mental Health. 🤓

That amazing, inspiring and wonderful day in my life followed a long and difficult journey that taught me not only how to succeed academically, but also gave me resilience to never give up on my hopes, dreams and goals for my life.

It was truly wonderful to be able to walk across the stage wearing my (often heavy) graduation gown to receive my Post-Graduate Diploma knowing that I had earned my place and belong to the King’s College London community (which I still sometimes find hard to believe even now).

Seeing all the other graduates that day walking across the stage inspired me knowing they, too, had endured and overcome their own individual journeys to be there.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu was quoted by one of the professors during the ceremony:

Do your little bit of good where you are; it’s those little bits of good put together that overwhelm the world.

It is my hope that the work I do at Formby Counselling will bring that ‘little bit of good’ that I feel I do together with the work of others that will overwhelm the world with good.

My qualification studied the space between psychology and neuroscience and taught me that a better understanding of how both these subjects work together can improve mental health.

The course gave me a sense of curiosity and fascination for neuroscience and how this could be integrated into my private practice as a psychotherapist at Formby Counselling.

psychotherapy and neuroscience

Let’s take a look now and dig a little deeper into the enduring love story between psychotherapy and neuroscience.

Once upon a time more than a century ago, psychotherapy and neuroscience met and went on a first date together in 1895. They were instantly attracted to each other and made a connection that can be traced back to the work of a neurologist who later became a psychotherapist.

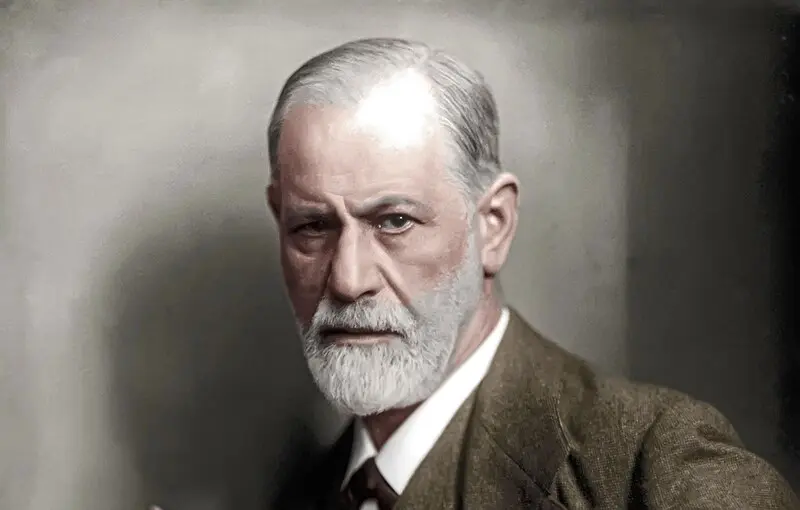

This was Dr Sigmund Freud whom we all can recognise now. The prospective partners got on really well with each other and promised to keep seeing each other and strengthening their initial connection in Freud’s unpublished article called Project for a Scientific Psychology in 1895. This article attempted to explain psychodynamic therapy concepts such as unconscious processes, early childhood experiences, and internal conflicts using a neurological framework.

However, after the initial ‘chemistry’ between psychotherapy and neuroscience, their love and connection for each other began to weaken as the technology of the time could not bridge the gap successfully between psychology of the mind with neurology of the brain, so the partners drifted apart and remained separated for most of the 20th century after Freud abandoned his innovative project altogether.

Despite the break-up of a very promising connection, Freud held a life-long hope that one day in the future psychotherapy and neuroscience would be reunited once neuroscience technological advances such as brain imaging techniques like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) became widely available making it possible for the structure and activity of our brains to be observed in real-time (neurofeedback that uses real-time displays of brain activity most commonly using electroencephalography (EEG)).

When the close partners of psychotherapy and neuroscience parted ways and separated in Freud’s era, these technical neuroscientific advances were only exciting almost ‘magical’ possibilities still the best part of a century away from becoming real that Freud could only dream about.

As we all know, the greatest love stories never truly end as the real love connection between psychotherapy and neuroscience never died. These perfectly matched partners endured the technological challenges of the 20th century and finally reunited in the 1990’s through the pioneering research of Dr Eric Kandel, an Austrian-born American medical doctor who specialised in psychiatry and was also a neuroscientist. Kandel’s work showed the psychological concepts of learning and memory are powered by neurological changes in electrical connections (synapses) between brain cells (neurons).

In the words so beautifully sung by the late Etta James, ‘At last, my love has come along, my lonely days are over and life is like a song’, and, at last, there was solid neurobiological proof to validate and celebrate the positive relationship between psychotherapy and neuroscience. At last, we finally understood how ‘talk therapy’ could actually create long-lasting structural and behavioural changes in our brains known as neuroplasticity which is one of the most exciting bridges between neuroscience and mental health treatment.

Once reunited, the perfectly compatible partners of psychotherapy and neuroscience continued to grow stronger in their relationship following the birth of neuropsychotherapy in the early 2000’s due to the work of Professor Dr. Klaus Grawe, a German psychologist and neuroscientist who laid the foundations for combining psychotherapy with a neuroscientific understanding of our brains.

The enduring love connection between perfectly matched partners of neuroscience and psychotherapy continued into the dawning of the 21st century as they celebrated the new Millenium firmly back together. The complementary and positive relationship between these partners has continued to shape modern mental health care in powerful ways today.

Psychotherapy provides healing through talking about problems and difficulties to focus on and gain emotional and behavioural changes, cognitive restructuring (changing thought patterns), relationship dynamics (patterns of behaviour and interactions between people), coping strategies and psychological resilience that strengthens neural/brain cell networks linked with executive function (helps us plan, focus attention, remember instructions, and manage multiple tasks successfully) and stress tolerance.

Psychotherapy is the perfectly matched partner with neuroscience which gives us knowledge of brain structure and function, how neurochemical messengers in our brains create and change our emotions, thoughts and behaviours, how our brains are constantly changing and growing through knowledge gained from previous experiences, (neuroplasticity which is the brain’s ability to reorganise itself by forming new neural/brain cell connections, strengthen or weaken existing neural connections based on experience, recover from injury or adapt to new learning), how psychotherapy can lead to physical and functional changes in the brain through neuroplasticity, and an understanding of the biological ‘bookmarks’ for mental health conditions.

Essentially, neuroscience sheds light on why psychotherapy works such as how talking about trauma, re-experiencing it in our bodies in small amounts of time that we can control and cope with in a safe and structured psychotherapeutic setting can reduce over-activity in the amygdala area of our brains which can be seen on fMRI brain imaging that shows changes in the activity of our brain structures. Psychotherapy can also be meaningfully ‘matched’ with other supportive partners such as neurofeedback, mindfulness (paying attention to the present moment with openness, curiosity, and without judgment) or pharmacological support (taking GP prescribed anti-depressant or anti-anxiety/anxiolytic medications).

Psychotherapists who are informed by a knowledge of neuroscience may better understand neurodiversity (autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder), developmental stages in childhood, attachment (how close bonds with parents/caregivers are formed in childhood and how obstacles/interruptions can change these close bonds), and how trauma can change brain development.

This appreciation of neuroscience can encourage hope and motivation empowering psychotherapists and clients to know change is not just possible, it’s physical.